Showing posts with label bipolar disorder. Show all posts

Showing posts with label bipolar disorder. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 2, 2012

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Now Available as a Paperback

From Therese Borchard, author of Beyond Blue:

From Therese Borchard, author of Beyond Blue:I kept saying to myself, "Did he just write that?" "Did he really just write that?" until I got to the third chapter and expected the pages ahead to be full of the same playful, entertaining .... um .... original prose that preceded it.

Anyone can jot down the bizarre thought patterns that are floating between their brain lobes. I guess what makes McManamy different is that he has taken a tour of Dante's Inferno and, while there, jotted down some funny notes that people who had been to Dante's Purgatory--or maybe even the first layer of hell--might appreciate, read in the bathroom, or digest like their favorite comics because the stories simply make them feel better. They are written by an intelligent man who has suffered and has been able to translate that suffering into hysterical laughter.

Funny is good. And this man's outrageous stories make me laugh. Sometimes they even make me forget about my day's trauma. Now that's a miracle.

Purchase paperback edition ($9.95)

Or download directly to your Kindle or Kindle app ($4.99):

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Epigenetics and Mental Illness and You

Two posts ago, I took Robert Whitaker to task for misreporting an NIMH-funded study in order to advance his own idiosyncratic agenda. Whitaker reported the study as a garden variety postmortem exam of brains of those with schizophrenia vs controls. The study, in fact, involved epigenetics, which Whitaker both failed to mention and displayed no knowledge of.

I first came across the field in late 2003, which I reported soon after in an email newsletter and a month or two later in an article on mcmanweb. Last year, I folded the piece into a reworked article on genes. Back in 2003, like just about everyone else, I treated epigenetics as a sideshow - worth knowing about but not worth missing the latest American Idol over. Now, it is abundantly clear that epigenetics is emerging as the main event.

Lately, I've been running across reminders that I need to put a match to all my website content on genetics and start over, with epigenetics front-center. Great, a mammoth science project. In the meantime, here is my original piece ...

The conventional wisdom on genes goes something like this: DNA is transcribed onto RNA, which form proteins, which are responsible for just about every process in the body, from eye color to ability to fight off illness. But even as the finishing touches were being applied to the sequencing of the human genome (completed in April 2003), unaccountable anomalies kept creeping in, strangely reminiscent of the quarks and dark matter and sundry weird forces that keep muddying the waters of theoretical physics.

Enter the science of epigenetics, which attempts to explain the mysterious inner layers of the genetic onion that may account for why identical twins aren't exactly identical and other conundrums, including why some people are predisposed to mental illness while others are not. Scientific American devoted a two-part article to the topic in its November and December 2003 issues. To summarize:

Only two percent of our DNA - via RNA - codes for proteins. Until very recently, the rest was considered "junk," the byproduct of millions of years of evolution. Now scientists are discovering that some of this junk DNA switches on RNA that may do the work of proteins and interact with other genetic material. "Malfunctions in RNA-only genes," explains Scientific American, "can inflict serious damage."

Epigenetics delves deeper into the onion, involving "information stored in the proteins and chemicals that surround and stick to DNA." Methylation is a chemical process that, among other things, aids in the transcription of DNA to RNA and is believed to defend the genome against parasitic genetic elements called transpons. A 2003 MIT study created mice with an inborn deficiency of a methylating enzyme. Eighty percent of these mice died of cancer within nine months.

A late 2003 PubMed search of epigenetics and bipolar disorder revealed but two articles. A Jan 16, 2011 search turned up 83. Arturas Petronis MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto authored both of the 2003 articles. In one of them, he filled in some of the blanks:

We know that there is a high concordance of identical twins with bipolar disorder, but epigenetics, he explains, may account for the 30 to 70 percent of cases where only one twin has the illness.

Identical twins share the same DNA, but their epigenetic material may be different. Moreover, whereas DNA variations are permanent, epigenetic changes are in a process of flux and generally accumulate over time. This may explain, Dr Petronis theorizes, why bipolar disorder tends to manifest at ages 20–30 and 45-50, which coincides with major hormonal changes, which may "substantially affect regulation of genes ... via their epigenetic modifications."

The dynamics of epigenetic changes may also account for the fluctuating course of bipolar, Dr Petronis speculates, perhaps more so than static DNA variations.

Finally, as Scientific American points out, the fact that epigenetic anomalies can be reversed makes them inviting targets for a new generation of meds.

In a 2003 pilot study, Dr Petronis and his colleagues investigated the epigenetic gene modification in a section of the dopamine 2 receptor genes in two pairs of identical twins, one pair with both partners having schizophrenia and the other having only one partner with the illness. What they discovered was that the partner with schizophrenia from the mixed pair had more in common, epigenetically, with the other set of twins than his own unaffected twin.

Check out this 2010 Time Magazine piece on epigenetics.

I first came across the field in late 2003, which I reported soon after in an email newsletter and a month or two later in an article on mcmanweb. Last year, I folded the piece into a reworked article on genes. Back in 2003, like just about everyone else, I treated epigenetics as a sideshow - worth knowing about but not worth missing the latest American Idol over. Now, it is abundantly clear that epigenetics is emerging as the main event.

Lately, I've been running across reminders that I need to put a match to all my website content on genetics and start over, with epigenetics front-center. Great, a mammoth science project. In the meantime, here is my original piece ...

The conventional wisdom on genes goes something like this: DNA is transcribed onto RNA, which form proteins, which are responsible for just about every process in the body, from eye color to ability to fight off illness. But even as the finishing touches were being applied to the sequencing of the human genome (completed in April 2003), unaccountable anomalies kept creeping in, strangely reminiscent of the quarks and dark matter and sundry weird forces that keep muddying the waters of theoretical physics.

Enter the science of epigenetics, which attempts to explain the mysterious inner layers of the genetic onion that may account for why identical twins aren't exactly identical and other conundrums, including why some people are predisposed to mental illness while others are not. Scientific American devoted a two-part article to the topic in its November and December 2003 issues. To summarize:

Only two percent of our DNA - via RNA - codes for proteins. Until very recently, the rest was considered "junk," the byproduct of millions of years of evolution. Now scientists are discovering that some of this junk DNA switches on RNA that may do the work of proteins and interact with other genetic material. "Malfunctions in RNA-only genes," explains Scientific American, "can inflict serious damage."

Epigenetics delves deeper into the onion, involving "information stored in the proteins and chemicals that surround and stick to DNA." Methylation is a chemical process that, among other things, aids in the transcription of DNA to RNA and is believed to defend the genome against parasitic genetic elements called transpons. A 2003 MIT study created mice with an inborn deficiency of a methylating enzyme. Eighty percent of these mice died of cancer within nine months.

A late 2003 PubMed search of epigenetics and bipolar disorder revealed but two articles. A Jan 16, 2011 search turned up 83. Arturas Petronis MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto authored both of the 2003 articles. In one of them, he filled in some of the blanks:

We know that there is a high concordance of identical twins with bipolar disorder, but epigenetics, he explains, may account for the 30 to 70 percent of cases where only one twin has the illness.

Identical twins share the same DNA, but their epigenetic material may be different. Moreover, whereas DNA variations are permanent, epigenetic changes are in a process of flux and generally accumulate over time. This may explain, Dr Petronis theorizes, why bipolar disorder tends to manifest at ages 20–30 and 45-50, which coincides with major hormonal changes, which may "substantially affect regulation of genes ... via their epigenetic modifications."

The dynamics of epigenetic changes may also account for the fluctuating course of bipolar, Dr Petronis speculates, perhaps more so than static DNA variations.

Finally, as Scientific American points out, the fact that epigenetic anomalies can be reversed makes them inviting targets for a new generation of meds.

In a 2003 pilot study, Dr Petronis and his colleagues investigated the epigenetic gene modification in a section of the dopamine 2 receptor genes in two pairs of identical twins, one pair with both partners having schizophrenia and the other having only one partner with the illness. What they discovered was that the partner with schizophrenia from the mixed pair had more in common, epigenetically, with the other set of twins than his own unaffected twin.

Check out this 2010 Time Magazine piece on epigenetics.

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

Challenging the Bipolar-Sex Conventional Wisdom

I just added a new article to mcmanweb, The Whole Bipolar Sex Thing, which had its genesis in a series of posts on HealthCentral. Following is an extract ...

The conventional wisdom is that (hypo)mania increases our sexual drive - often to the point of excess - while depression has the opposite effect. Goodwin and Jamison in their 2007 "Manic-Depressive Illness" note that Aretaeus of Cappadocia in the second century AD observed "a period of lewdness and shamelessness exists in the highest type of [manic] delirium."

The authors cite a number of studies showing increased sexual interest and behavior during mania or hypomania, and the DSM makes it official by including "sexual indiscretions" in manic and hypomanic episodes. It also notes "decrease in sexual interests or drive" during depression.

Okay, time to challenge that notion. A 2006 NIH-funded study of a large teen population found that those who were depressed were far more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as drug use and sex. The study corroborates earlier findings.

One aspect of depression is a feeling of being "clinically dead but breathing," the very opposite of the "feeling alive" states of mind we experience in pure mania and hypomania. But something else also tends to be going on - intense psychic pain. If the clinically dead aspect of depression is about feeling too little, our psychic pain is about feeling too much. In this tortured state of mind we tend to be desperate for release, and seek it in a variety of ways - from attempting suicide to over-eating and over-sleeping to alcohol and drug abuse to "retail therapy" to the flood of feel-good hormones from a warm embrace.

The feeling may quickly wear off, but so what? People who have never experienced depression cannot possibly understand.

Thus both sides of the bipolar equation find us at risk, up as well as down. Yes, it is true that we are more likely to lose interest in sex when we are depressed, but this should not mask the fact that in certain instances the very opposite may occur, replete with the full menu of life-altering consequences. Psychic pain has that kind of effect on us.

Do Bipolars Make the Best Lovers?

Does hypersexuality in mania and hypomania actually translate to being better in bed? We have no evidence.

What is reasonable to assume is that our ups intensify all our experiences, whether listening to music, enjoying food, watching a sunset, or having sex. Even our downs can add layers of richness to our existence.

But is it possible for those close to us to experience our subjective realities? The answer appears appears to be yes. Our states of mind can be contagious. Wrote Kay Jamison of Virginia Woof, citing one of her social circle: "I always felt on leaving her that I had drunk two excellent glasses of champagne. She was a life-enhancer."

But the very intensity of our world can also be very frightening to others. Virginia Woolf may have lit up her Bloomsbury circle, but she also drove poor husband Leonard nuts. Likewise, the intensity factor has a way of drowning out the rest of our surroundings, including the people around us.

So - let's make a few wild guesses about what happens when we take our enhanced subjective realities to the bedroom. When things go right, it appears that the intensity we bring to the moment jumpstarts the "normal" partner's intensity, and next thing both partners are experiencing the type of cosmic union you read about in the poetry of Rumi.

Sample verse: "You are the sky my spirit circles in."

But maybe things get too intense for the comfort of our partner, perhaps to the point where he or she no longer feels safe. Maybe we are so into our own needs and desires that we lose sensitivity to those of our partner. We fail to pick up vital signals. We fail to make the necessary adjustments. Sex is mind-blowing enough without adding bipolar to it. Thus, if we are prepared to brag about how bipolars make the best lovers, we also need to accept the fact that there are times when we are probably the worst.

The "Bipolar-By-Proxy" Complication

Jumpstarting our partners may have the effect of turning them into "bipolar-by-proxy." This is wildly speculative, but let's run with it. If our partner is feeling the same kind of intensity we are feeling, with similar dopamine surges, then their capacity to make rational decisions may be as impaired as ours, perhaps more so. We at least have an experiential context to place our current state of intensity. Our partner may confuse this novel experience with love.

For the full article, check out The Whole Bipolar Sex Thing

The conventional wisdom is that (hypo)mania increases our sexual drive - often to the point of excess - while depression has the opposite effect. Goodwin and Jamison in their 2007 "Manic-Depressive Illness" note that Aretaeus of Cappadocia in the second century AD observed "a period of lewdness and shamelessness exists in the highest type of [manic] delirium."

The authors cite a number of studies showing increased sexual interest and behavior during mania or hypomania, and the DSM makes it official by including "sexual indiscretions" in manic and hypomanic episodes. It also notes "decrease in sexual interests or drive" during depression.

Okay, time to challenge that notion. A 2006 NIH-funded study of a large teen population found that those who were depressed were far more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as drug use and sex. The study corroborates earlier findings.

One aspect of depression is a feeling of being "clinically dead but breathing," the very opposite of the "feeling alive" states of mind we experience in pure mania and hypomania. But something else also tends to be going on - intense psychic pain. If the clinically dead aspect of depression is about feeling too little, our psychic pain is about feeling too much. In this tortured state of mind we tend to be desperate for release, and seek it in a variety of ways - from attempting suicide to over-eating and over-sleeping to alcohol and drug abuse to "retail therapy" to the flood of feel-good hormones from a warm embrace.

The feeling may quickly wear off, but so what? People who have never experienced depression cannot possibly understand.

Thus both sides of the bipolar equation find us at risk, up as well as down. Yes, it is true that we are more likely to lose interest in sex when we are depressed, but this should not mask the fact that in certain instances the very opposite may occur, replete with the full menu of life-altering consequences. Psychic pain has that kind of effect on us.

Do Bipolars Make the Best Lovers?

Does hypersexuality in mania and hypomania actually translate to being better in bed? We have no evidence.

What is reasonable to assume is that our ups intensify all our experiences, whether listening to music, enjoying food, watching a sunset, or having sex. Even our downs can add layers of richness to our existence.

But is it possible for those close to us to experience our subjective realities? The answer appears appears to be yes. Our states of mind can be contagious. Wrote Kay Jamison of Virginia Woof, citing one of her social circle: "I always felt on leaving her that I had drunk two excellent glasses of champagne. She was a life-enhancer."

But the very intensity of our world can also be very frightening to others. Virginia Woolf may have lit up her Bloomsbury circle, but she also drove poor husband Leonard nuts. Likewise, the intensity factor has a way of drowning out the rest of our surroundings, including the people around us.

So - let's make a few wild guesses about what happens when we take our enhanced subjective realities to the bedroom. When things go right, it appears that the intensity we bring to the moment jumpstarts the "normal" partner's intensity, and next thing both partners are experiencing the type of cosmic union you read about in the poetry of Rumi.

Sample verse: "You are the sky my spirit circles in."

But maybe things get too intense for the comfort of our partner, perhaps to the point where he or she no longer feels safe. Maybe we are so into our own needs and desires that we lose sensitivity to those of our partner. We fail to pick up vital signals. We fail to make the necessary adjustments. Sex is mind-blowing enough without adding bipolar to it. Thus, if we are prepared to brag about how bipolars make the best lovers, we also need to accept the fact that there are times when we are probably the worst.

The "Bipolar-By-Proxy" Complication

Jumpstarting our partners may have the effect of turning them into "bipolar-by-proxy." This is wildly speculative, but let's run with it. If our partner is feeling the same kind of intensity we are feeling, with similar dopamine surges, then their capacity to make rational decisions may be as impaired as ours, perhaps more so. We at least have an experiential context to place our current state of intensity. Our partner may confuse this novel experience with love.

For the full article, check out The Whole Bipolar Sex Thing

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Ten Thousand Ways Our Brains Are Messed Up

One of the major stories in bipolar over the past decade is the growing recognition that the condition is way more than a mood disorder. On one hand, we are talking about the thinking cortical regions that fail to boot up properly, even in euthymic (well) patients. On the other, we are talking about the reactive limbic regions that boot up all too well. Too frequently the neural networks that connect the two are severely compromised. Bad things happen.

At the 9th International Bipolar Conference that wrapped up on Sunday, Stephen Strakowski of the University of Cincinnati presented the equivalent of a master’s class.

Above is a representation of the anterior limbic network (ALN). Forget for the time being about specific brain regions and which region is responsible for what. Instead, check out the arrows in the picture that represent how these regions talk and cross-talk with one another. In a 2006 article on CNS Spectrums, Dr Strakowski refers to the old brain science as a “form of phrenology” that wrongly suggested that specific portions of the brain are associated with specific cognitive and emotional traits. Rather:

More recent neuroimaging studies suggest that emotion regulation is an emergent phenomenon that arises out of specific neural networks and that bipolar disorder represents the consequences of dysregulation in these networks.

Okay, let’s see how this works. In a 2004 brain scan study, euthymic bipolar patients performed as well on a simple cognitive task as the healthy controls, but to keep up the bipolars had to activate more brain regions. Dr Strakowski in his talk disclosed he had originally misinterpreted the results. What happened, he said, on later reflection was that the amygdala (which mediates arousal and fear) in the bipolar subjects lit up like a Christmas tree. To compensate for the over-active amygdala, the bipolars recruited the ventral medial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC). Image below.

So, even in routine situations, our brains are subject to stress. And to make up for it, we have to work the thinking parts of the brain harder. No harm, no foul, right?

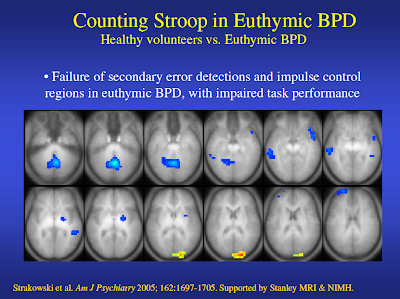

In another experiment, Stakowski and his colleagues turned up the heat. This time, the subjects were put through a more complex cognitive task called the “counting Stroop,” which involves sorting out incongruent images in rapid succession (such as the number four spelled out three times). In this task, the bipolars scored rather worse than the healthy controls.

Here’s where it really gets interesting. As the task got more difficult, the controls were successful in easing back and slowing down their reaction times, allowing them precious micro-seconds to bring the cognitive areas of the brain online, in particular the regions involved in impulse-control. The bipolars, by contrast, failed miserably in this regard. They kept plowing ahead.

In another study, involving a facial recognition task, Strakowski and his colleagues found difficulties in bipolars in recruiting the VMPFC to suppress amygdala over-activity, resulting in loss of prefrontal control over the brain. In yet another study, the cingulate in the midbrain failed to sort out background noise. On and on it went.

So, imagine yourself in a crowded room this time, not in a brain scan machine. Even the routine task of talking to someone you feel comfortable with may be stressful. Then a stranger sidles over. Meanwhile, you are finding it difficult to tune out a million and one things going on in the room. Everything seems to be closing in. Then your mother-in-law barges in and starts yapping away.

Maybe you rise to the occasion and handle the situation superbly. But you know there is going to be hell to pay some time later. In all likelihood, you will arrive home, either feeling like a wrung-out dish rag or with racing thoughts - or maybe both - needing at least a precious day of recovery time you don’t have. Heaven forbid if you have an important meeting with your boss first thing in the morning.

Obviously, the recovery techniques we have at our disposal help enormously - from the tricks we pick up in cognitive-behavioral therapy to mindfulness to stopping to smell the roses. But when I addressed the panel on the topic of skills training, I was met with blank stares. Here’s where I am coming from:

Two years ago, at the International Congress on Schizophrenia, I happened to walk into a session entitled, "Optimizing Cognitive Training Approaches in Schizophrenia." From a blog piece, Figuring Our Schizophrenia, I did soon after ...

Translation: The brain is plastic. As Michael Merzenich of UCSF describes it, "Basically, we create ourselves."

The brain is born stupid, then evolves and becomes "massively optimized to fit into your world."

In recognition of this, a relatively new field is opening up that involves drilling patients in cognitive tasks we tend to take for granted, such as holding a thought in our working memory long enough to lay down new neural roadwork or responding to stimuli in a timely fashion.

New computer programs are being developed and being tested on patients, Sophia Vinogradov of UCSF explains, and we are seeing enduring changes in the cognitive performance of patients six months later.

Naturally, I was flabbergasted to find the panelists at the Bipolar Conference wholly ignorant to this, but then again I wasn’t surprised. Despite the fact that the schizophrenia researchers are light-years ahead of the bipolar researchers (aided by infinitely more research dollars) bipolar researchers do not seek them out. Carol Tamminga of the University of Texas, a prominent schizophrenia researcher, was far more polite when she addressed the Bipolar Conference four years earlier, simply referring to the lack of cross-talk between the two fields.

Fortunately, after the seminar, someone sought me out and validated my query, referring to Dr Merzenich and a website involving his work called positscience, which provides some online samples of these cognitive drills. Bipolar is five years behind schizophrenia, my informant acknowledged.

One more point: The studies Dr Strakowski and others perform are designed to catch us at our cognitive worst. These studies are comparatively easy to design and execute. Studies that would catch us at our best - formulating a creative response, thinking outside the box, reaching an intuitive insight - simply do not exist. We know our brains are precision-tooled for this, and researchers such as Nancy Andreasen of the University of Iowa are studying the phenomena very intently. But there is no way to capture the birth of a creative idea in a brain scan machine.

But at least a picture - good and bad - is beginning to emerge of what is going on beneath the hood. And in this type of self-knowledge lies the key to leading more fulfilling lives than we could have imagined when we were initially blindsided by this illness. Be hopeful. Knowledge is necessity.

At the 9th International Bipolar Conference that wrapped up on Sunday, Stephen Strakowski of the University of Cincinnati presented the equivalent of a master’s class.

Above is a representation of the anterior limbic network (ALN). Forget for the time being about specific brain regions and which region is responsible for what. Instead, check out the arrows in the picture that represent how these regions talk and cross-talk with one another. In a 2006 article on CNS Spectrums, Dr Strakowski refers to the old brain science as a “form of phrenology” that wrongly suggested that specific portions of the brain are associated with specific cognitive and emotional traits. Rather:

More recent neuroimaging studies suggest that emotion regulation is an emergent phenomenon that arises out of specific neural networks and that bipolar disorder represents the consequences of dysregulation in these networks.

Okay, let’s see how this works. In a 2004 brain scan study, euthymic bipolar patients performed as well on a simple cognitive task as the healthy controls, but to keep up the bipolars had to activate more brain regions. Dr Strakowski in his talk disclosed he had originally misinterpreted the results. What happened, he said, on later reflection was that the amygdala (which mediates arousal and fear) in the bipolar subjects lit up like a Christmas tree. To compensate for the over-active amygdala, the bipolars recruited the ventral medial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC). Image below.

So, even in routine situations, our brains are subject to stress. And to make up for it, we have to work the thinking parts of the brain harder. No harm, no foul, right?

In another experiment, Stakowski and his colleagues turned up the heat. This time, the subjects were put through a more complex cognitive task called the “counting Stroop,” which involves sorting out incongruent images in rapid succession (such as the number four spelled out three times). In this task, the bipolars scored rather worse than the healthy controls.

Here’s where it really gets interesting. As the task got more difficult, the controls were successful in easing back and slowing down their reaction times, allowing them precious micro-seconds to bring the cognitive areas of the brain online, in particular the regions involved in impulse-control. The bipolars, by contrast, failed miserably in this regard. They kept plowing ahead.

In another study, involving a facial recognition task, Strakowski and his colleagues found difficulties in bipolars in recruiting the VMPFC to suppress amygdala over-activity, resulting in loss of prefrontal control over the brain. In yet another study, the cingulate in the midbrain failed to sort out background noise. On and on it went.

So, imagine yourself in a crowded room this time, not in a brain scan machine. Even the routine task of talking to someone you feel comfortable with may be stressful. Then a stranger sidles over. Meanwhile, you are finding it difficult to tune out a million and one things going on in the room. Everything seems to be closing in. Then your mother-in-law barges in and starts yapping away.

Maybe you rise to the occasion and handle the situation superbly. But you know there is going to be hell to pay some time later. In all likelihood, you will arrive home, either feeling like a wrung-out dish rag or with racing thoughts - or maybe both - needing at least a precious day of recovery time you don’t have. Heaven forbid if you have an important meeting with your boss first thing in the morning.

Obviously, the recovery techniques we have at our disposal help enormously - from the tricks we pick up in cognitive-behavioral therapy to mindfulness to stopping to smell the roses. But when I addressed the panel on the topic of skills training, I was met with blank stares. Here’s where I am coming from:

Two years ago, at the International Congress on Schizophrenia, I happened to walk into a session entitled, "Optimizing Cognitive Training Approaches in Schizophrenia." From a blog piece, Figuring Our Schizophrenia, I did soon after ...

Translation: The brain is plastic. As Michael Merzenich of UCSF describes it, "Basically, we create ourselves."

The brain is born stupid, then evolves and becomes "massively optimized to fit into your world."

In recognition of this, a relatively new field is opening up that involves drilling patients in cognitive tasks we tend to take for granted, such as holding a thought in our working memory long enough to lay down new neural roadwork or responding to stimuli in a timely fashion.

New computer programs are being developed and being tested on patients, Sophia Vinogradov of UCSF explains, and we are seeing enduring changes in the cognitive performance of patients six months later.

Naturally, I was flabbergasted to find the panelists at the Bipolar Conference wholly ignorant to this, but then again I wasn’t surprised. Despite the fact that the schizophrenia researchers are light-years ahead of the bipolar researchers (aided by infinitely more research dollars) bipolar researchers do not seek them out. Carol Tamminga of the University of Texas, a prominent schizophrenia researcher, was far more polite when she addressed the Bipolar Conference four years earlier, simply referring to the lack of cross-talk between the two fields.

Fortunately, after the seminar, someone sought me out and validated my query, referring to Dr Merzenich and a website involving his work called positscience, which provides some online samples of these cognitive drills. Bipolar is five years behind schizophrenia, my informant acknowledged.

One more point: The studies Dr Strakowski and others perform are designed to catch us at our cognitive worst. These studies are comparatively easy to design and execute. Studies that would catch us at our best - formulating a creative response, thinking outside the box, reaching an intuitive insight - simply do not exist. We know our brains are precision-tooled for this, and researchers such as Nancy Andreasen of the University of Iowa are studying the phenomena very intently. But there is no way to capture the birth of a creative idea in a brain scan machine.

But at least a picture - good and bad - is beginning to emerge of what is going on beneath the hood. And in this type of self-knowledge lies the key to leading more fulfilling lives than we could have imagined when we were initially blindsided by this illness. Be hopeful. Knowledge is necessity.

Labels:

bipolar disorder,

brain science,

John McManamy,

Strakowski

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Your Bipolar - Not Your Grandfather's Bipolar

As you know, I'm trashing most of the articles in the Treatment section to mcmanweb and writing entirely new ones. Yesterday, I presented a sneak preview to one, The Problem with Bipolar Meds. Today, I managed to come up with a satisfactory introduction to it. Without further ado ...

When I was first diagnosed with bipolar at age 49 in 1999 (after a lifetime of denial), I was told by numerous clinicians and well-meaning lay people that my illness was highly treatable, a message reinforced by just about everything I read. I'm not saying these individuals lied to me, but the reality is rather different. Two explanations are in play:

First, doctors and researchers have a very different idea of successful treatment than patients. Clinical trials are based on the artificial criteria of symptom-reduction rather than return to function. Meanwhile, doctors are content to leave us in a state of over-medicated limbo - stable but not well, out of crisis but going nowhere.

The other explanation is that your bipolar is not your father's bipolar or your grandfather's bipolar. "The illness has been altered," Frederick Goodwin MD, former head of the NIMH, informed a session at the American Psychiatric Meeting in 2008, with more rapid-cycling, mixed states, and other complications since the first edition to his classic "Manic-Depressive Illness" came out in 1990. We have no definitive answer, but the best guess by far (which Dr Goodwin advances) has been the indiscriminate use of antidepressants, which he declared a "disaster" for one-third of us.

This may account for the disconnect between the memoirs of Kay Jamison and Patty Duke, writing about their experiences at least two decades before SSRIs came on the scene, and the accounts you hear today walking into support groups. Lithium was the miracle med for both authors. Today, lithium has only half the success rate it had back when Dr Jamison and Ms Duke were put on the med.

The harsh reality is that despite spectacular advances in our understanding of the brain and mental illness, our doctors appear at a loss in how to treat us. Your best chance of success is coming to terms with this grim fact of life so you can make intelligent choices.

When I was first diagnosed with bipolar at age 49 in 1999 (after a lifetime of denial), I was told by numerous clinicians and well-meaning lay people that my illness was highly treatable, a message reinforced by just about everything I read. I'm not saying these individuals lied to me, but the reality is rather different. Two explanations are in play:

First, doctors and researchers have a very different idea of successful treatment than patients. Clinical trials are based on the artificial criteria of symptom-reduction rather than return to function. Meanwhile, doctors are content to leave us in a state of over-medicated limbo - stable but not well, out of crisis but going nowhere.

The other explanation is that your bipolar is not your father's bipolar or your grandfather's bipolar. "The illness has been altered," Frederick Goodwin MD, former head of the NIMH, informed a session at the American Psychiatric Meeting in 2008, with more rapid-cycling, mixed states, and other complications since the first edition to his classic "Manic-Depressive Illness" came out in 1990. We have no definitive answer, but the best guess by far (which Dr Goodwin advances) has been the indiscriminate use of antidepressants, which he declared a "disaster" for one-third of us.

This may account for the disconnect between the memoirs of Kay Jamison and Patty Duke, writing about their experiences at least two decades before SSRIs came on the scene, and the accounts you hear today walking into support groups. Lithium was the miracle med for both authors. Today, lithium has only half the success rate it had back when Dr Jamison and Ms Duke were put on the med.

The harsh reality is that despite spectacular advances in our understanding of the brain and mental illness, our doctors appear at a loss in how to treat us. Your best chance of success is coming to terms with this grim fact of life so you can make intelligent choices.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Rerun: Misdiagnosis - Patients Tell Their Stories

My recent five-part (and counting) series, Are Antidepressants Bad For You?, noted that a large part of the problem has to do with physicians blindly treating anything that resembles a depression with these meds, often with disastrous results. This piece from a year ago elaborates ...

I write a very different blog on HealthCentral's BipolarConnect. There, I take a backseat to my readers, bipolar patients and loved ones. Nearly a month ago, I asked them:

Were you misdiagnosed with depression or something else? How long did it take before you finally received the correct diagnosis?

Readers began telling their stories over the next days and weeks, which I assembled into three blog pieces. The narrative is sobering and instructional:

"Jane's" response is fairly typical. She was diagnosed with depression at age 16 and prescribed Zoloft, “which was making me like a bunny on mass caffeine consumption.” She was put on Paxil, but her depression worsened and she gained 40 pounds. Unable to hold onto her job, she found a new doc, who “cocked his head, asked about my family’s mental health history ... and asked me ‘Did anyone ever ask you if you thought you might be bipolar?’"

Finally, on Lamictal, she has her life back, but "I spent 11 years on the wrong meds and destroying my life because I was misdiagnosed.”

What is coming in loud and clear is that a misdiagnosis of depression is all too common, with years on antidepressants that only worsen one's unrecognized bipolar. Since we tend to seek help when we are depressed rather than manic, it is not surprising that we receive the wrong diagnosis at first instance. But then the problem is compounded by psychiatrists who refuse to listen. As "Rachel," who waited 14 years for the correct diagnosis, describes it:

My major complaint with this whole debacle is not that I was incorrectly medicated, it is that I was incorrectly medicated because an entire comprehensive mental and physical inventory was never taken. AKA no one ever TALKED to me about what I was feeling and why I was feeling it. No one had mined my data for facts and established a clear pattern of my behavior. The first person who did that was me. ... They didn't do their job. Much like getting a bad mechanic job, my tranny dropped out on the freeway and my vehicle hit the wall going 75 - a complete loss.

Doctors who don't listen - that has been by far the number one complaint I have received from readers ever since I began writing about bipolar more than 10 years ago. As "Lorraine," who suffered with antidepressants for three years, writes:

The doctor (as many are) was a know-it-all and rarely listened to me. The doctor rarely considered how I felt. The doctor thought no one could ever know more than this one. The doctor rarely even considered the possibility of what I was feeling.

Why does it take so long for doctors to get smart? "Georgine" responds: "I believe it was because I was diagnosed with [depression] before so instead of trying to find out what I needed, the docs took the previous diagnosis and just agreed with it."

It took 25 years before a doctor finally corrected the original error.

And this from "Eva":

It was only when I got old and ugly that a doctor finally said, ya man, she's depressed, and she's bipolar. ... When I was young, beautiful and well-groomed, I looked like a female high-powered executive. On top of the world to the doctors who saw me. They dismissed my claims of depression, as ridiculousness. What does she have to be depressed about? Now that I'm old, ugly, unfashionable, I'm believable.

Our own ignorance and denial is another factor. As "Lilly" reports: “I stayed in denial successfully with alcohol and pills.” At last, during her third hospitalization, “I finally opened up a pamphlet on bipolar.” She took her meds as directed, and “was able to see reason. ... I’ve been struggling with this disease for over 25 years since I had turned 16 years old and I was 40 when I excepted it as something I would have to live with and take care of for the remainder of my life. Life is good now.”

***

There is no substitute for listening to real accounts from patients and loved ones. You can check out the full conversation at Bipolar Connect in the comments to my original question and a follow-up question, as well as my three pieces and the comments to these pieces:

Misdiagnosis - Eight Readers Tell Their Stories

Misdiagnosis - The Dialogue Continues

Misdiagnosis - Readers Tell Their Stories

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

My DSM-5 Report Card: Grading Bipolar - Part II

Part I began issuing grades on the homework handed in nearly two weeks ago by the DSM-5 Task Force concerning its proposed revisions to bipolar. To recap:

Depression - “What were these people thinking? They weren’t.” Grade: F-minus.

Euphoric and Dysphoric Mania - “Is there a secret DSM with accurate information that only a privileged few are allowed access to? And a fantasy DSM for all the rest of us?” Grade: F.

The Mania Minimum Time Limit - “Why seven days? Why not four? Who is truly counting the days when our life is in ruins? Don’t make me answer that.” Grade: D.

Hypomania as a Marker for Depression - “A very strong case can be made for lowering the diagnostic thresholds for hypomania.” Grade: Incomplete.

Hypomania as a Marker for Mania - “One simple adjustment. Are we asking for too much? Yes, apparently.” Grade: F.

Dysphoric and Euphoric Hypomania - “The same arguments that apply to mania apply here.” Grade: F.

Moving on ...

Antidepressant-Induced Mania/Hypomania

The DSM-5 would recognize that flipping into mania or hypomania as the result of an antidepressant or ECT or other depression treatment “is sufficient evidence for a manic or a hypomanic episode diagnosis,” but cautions that a mere one or two symptoms (such as irritability) should not be taken as evidence of an episode.

For a change, the DSM-5 Mood Disorders workgroup actually made what would amount to a significant change to the bipolar diagnosis. The catch is they buried it in the usual standard boilerplate which is suddenly not so standard. Trust me, if I failed to pick it up, the person you entrust your life to is not about to pick it up, either.

Grade: C-minus.

Mixed Episodes, Symptoms

In real life there are “pure” depressions and “mixed” depressions, “pure” manias and “mixed” manias. Successfully differentiating one from the other is crucial to treatment success. The current DSM recognizes mixed states only in bipolar I, when depression (with a capital D) and mania (with a capital M) rear their ugly heads together. Thus: DM.

Your best source of finding out what a mixed episode is like is listening to a patient who has been through it. Unbelievably, the DSM never bothered to turn in a description. (Short description: various forms of energized psychic distress, such as road rage, even when not driving.)

In by far the most significant change to the bipolar diagnosis, the DSM-5 would widen mixed states to include two or three mania symptoms (m) inside depression (D) or two or three depression symptoms (d) inside mania/hypomania (M). Thus: Dm or Md.

Presumably, this translates into symptoms strong enough to turn “euphoric” manias “dysphoric” and mind-numbing depressions “agitated.” The problem is the DSM leaves us presuming. Once again, what does a mixed state look like? Do we have to Google the answers, ourselves?

Grade: C-minus.

Mixed Episodes, Spectrum Considerations

The DSM-5 would acknowledge two types of mixed episodes: Predominately depressed and predominately manic/hypomanic, which would include for the first time those with bipolar II. The DSM-5 workgroup is undecided whether to include mixed states as episodes in their own right or as specifiers to depressive and manic episodes.

Inexcusably undecided is the workgroup’s position on mixed states in unipolar depression (see Part I to Grading Depression). Why would mixed depressions somehow be regarded as exclusive to the bipolar diagnosis?

Last but not least, why should a mixed depression or mania/hypomania require a full-blown episode? Think: how well are you truly when you have elements of both depression (d) and mania/hypomania (m) going on at once (dm)? Or, to put it another way, when is counting symptoms a substitute for evaluating functional impairments?

Grade: C-plus.

Bipolar III

Should the threshold for bipolar II be lowered to include patients with so-called “soft” bipolar? These are individuals whose depressions have far more in common with bipolar than unipolar and who do cycle “up,” though not necessarily as high or as long.

Or should a new category by created for them, such as bipolar III?

In other words, why should those who don’t dance on tables be overlooked? Especially if they continue to lead miserable lives treated as if for unipolar depression.

The DSM is considering reducing the time criteria for a hypomanic episode for bipolar II, but is holding the line on the symptom minimum.

Grade: D.

Recurrent Depression

As opposed to chronic depression, recurrent depressions come and go, typically in an up and down pattern. The current DSM includes recurrent depression as part unipolar depression and the DSM-5 would preserve the status quo.

Here’s the issue: If no expanded bipolar II diagnosis or no bipolar III, then why not put recurrent depression into service? Perhaps add new criteria as part of a new “highly recurrent depression” or “cycling depression” diagnosis. There are at least three advantages to this:

Grade: F-minus.

Rapid-Cycling

Strangely enough, true rapid-cyclers ride the roller coaster far too fast to be considered DSM-eligible as a rapid-cyclers, much less rate a bipolar diagnosis. Blame the current DSM for this mess, which demands the same “duration criteria” for episodes from everyone (two weeks for depression, one for mania, four days for hypomania).

According to an article in Psychiatric Times, even those responsible for the DSM-IV recognized the absurdity in their thinking. The question remains - can the DSM-5?

Grade: Incomplete.

Much more to come. Stay tuned for Part III ...

Depression - “What were these people thinking? They weren’t.” Grade: F-minus.

Euphoric and Dysphoric Mania - “Is there a secret DSM with accurate information that only a privileged few are allowed access to? And a fantasy DSM for all the rest of us?” Grade: F.

The Mania Minimum Time Limit - “Why seven days? Why not four? Who is truly counting the days when our life is in ruins? Don’t make me answer that.” Grade: D.

Hypomania as a Marker for Depression - “A very strong case can be made for lowering the diagnostic thresholds for hypomania.” Grade: Incomplete.

Hypomania as a Marker for Mania - “One simple adjustment. Are we asking for too much? Yes, apparently.” Grade: F.

Dysphoric and Euphoric Hypomania - “The same arguments that apply to mania apply here.” Grade: F.

Moving on ...

Antidepressant-Induced Mania/Hypomania

The DSM-5 would recognize that flipping into mania or hypomania as the result of an antidepressant or ECT or other depression treatment “is sufficient evidence for a manic or a hypomanic episode diagnosis,” but cautions that a mere one or two symptoms (such as irritability) should not be taken as evidence of an episode.

For a change, the DSM-5 Mood Disorders workgroup actually made what would amount to a significant change to the bipolar diagnosis. The catch is they buried it in the usual standard boilerplate which is suddenly not so standard. Trust me, if I failed to pick it up, the person you entrust your life to is not about to pick it up, either.

Grade: C-minus.

Mixed Episodes, Symptoms

In real life there are “pure” depressions and “mixed” depressions, “pure” manias and “mixed” manias. Successfully differentiating one from the other is crucial to treatment success. The current DSM recognizes mixed states only in bipolar I, when depression (with a capital D) and mania (with a capital M) rear their ugly heads together. Thus: DM.

Your best source of finding out what a mixed episode is like is listening to a patient who has been through it. Unbelievably, the DSM never bothered to turn in a description. (Short description: various forms of energized psychic distress, such as road rage, even when not driving.)

In by far the most significant change to the bipolar diagnosis, the DSM-5 would widen mixed states to include two or three mania symptoms (m) inside depression (D) or two or three depression symptoms (d) inside mania/hypomania (M). Thus: Dm or Md.

Presumably, this translates into symptoms strong enough to turn “euphoric” manias “dysphoric” and mind-numbing depressions “agitated.” The problem is the DSM leaves us presuming. Once again, what does a mixed state look like? Do we have to Google the answers, ourselves?

Grade: C-minus.

Mixed Episodes, Spectrum Considerations

The DSM-5 would acknowledge two types of mixed episodes: Predominately depressed and predominately manic/hypomanic, which would include for the first time those with bipolar II. The DSM-5 workgroup is undecided whether to include mixed states as episodes in their own right or as specifiers to depressive and manic episodes.

Inexcusably undecided is the workgroup’s position on mixed states in unipolar depression (see Part I to Grading Depression). Why would mixed depressions somehow be regarded as exclusive to the bipolar diagnosis?

Last but not least, why should a mixed depression or mania/hypomania require a full-blown episode? Think: how well are you truly when you have elements of both depression (d) and mania/hypomania (m) going on at once (dm)? Or, to put it another way, when is counting symptoms a substitute for evaluating functional impairments?

Grade: C-plus.

Bipolar III

Should the threshold for bipolar II be lowered to include patients with so-called “soft” bipolar? These are individuals whose depressions have far more in common with bipolar than unipolar and who do cycle “up,” though not necessarily as high or as long.

Or should a new category by created for them, such as bipolar III?

In other words, why should those who don’t dance on tables be overlooked? Especially if they continue to lead miserable lives treated as if for unipolar depression.

The DSM is considering reducing the time criteria for a hypomanic episode for bipolar II, but is holding the line on the symptom minimum.

Grade: D.

Recurrent Depression

As opposed to chronic depression, recurrent depressions come and go, typically in an up and down pattern. The current DSM includes recurrent depression as part unipolar depression and the DSM-5 would preserve the status quo.

Here’s the issue: If no expanded bipolar II diagnosis or no bipolar III, then why not put recurrent depression into service? Perhaps add new criteria as part of a new “highly recurrent depression” or “cycling depression” diagnosis. There are at least three advantages to this:

- This would recognize the bipolar nature of these depressions without necessarily acknowledging them as part of the bipolar diagnosis. Clinicians would be encouraged to investigate more closely for these type of depressions before indiscriminately prescribing antidepressants.

- Since this type of cycling depression would not be regarded as part of the bipolar diagnosis, a clinician need not find evidence of hypomania or mania to make the right call.

- A cycling depression diagnosis would avoid the stigma of a bipolar diagnosis.

Grade: F-minus.

Rapid-Cycling

Strangely enough, true rapid-cyclers ride the roller coaster far too fast to be considered DSM-eligible as a rapid-cyclers, much less rate a bipolar diagnosis. Blame the current DSM for this mess, which demands the same “duration criteria” for episodes from everyone (two weeks for depression, one for mania, four days for hypomania).

According to an article in Psychiatric Times, even those responsible for the DSM-IV recognized the absurdity in their thinking. The question remains - can the DSM-5?

Grade: Incomplete.

Much more to come. Stay tuned for Part III ...

Sunday, February 7, 2010

Pete Earley - Outrage in Fairfax

Pete Earley is the author of the highly-acclaimed “Crazy: A Father’s Search Through America’s Mental Health Madness.” Prior to turning his attention to mental illness, Pete, a former Washington Post investigative journalist, had achieved fame writing books on such topics as crime, criminal justice, Vegas, and spies. Then, one day, out of nowhere, ten tons of bricks dropped on his head.

Several years ago, Pete stood by helpless as his son Mike, fresh out of college, went off his Zyprexa and flipped into florid psychosis. But for doctors to treat him, first they needed his consent. Never mind that Mike’s condition had robbed his brain of all power to reason. Rules are rules. Of course, should Pete's son do something outrageous ...

A couple of days later, Mike obliged. In a highly delusional state, he broke into someone’s home and took a bubble bath. It took six Fairfax County (VA) police and a police dog to subdue him. Now a felony charge hung over Pete’s son. As Pete explained to a session I attended at the 2006 NAMI convention: “We’ve made them criminals as well as mentally ill.”

Pete’s wife urged him to do as a journalist what he could not do as a parent. Driven by his family nightmare, Pete did his own homework and turned in an eye-opening account of the degradation and horror visited upon those left to fend for themselves.

I’ve had occasion to meet up with Pete twice since then. (Pete was highly complimentary of my own book, and provided me, unsolicited, with a ringing endorsement.) He’s in high demand as a speaker at mental health conferences, and when he talks he leaves no doubt that the fire burns hot in his belly. Same with when he writes.

Yesterday’s Washington Post features an op-ed piece by Pete. According to the facts he presents:

In November, David Masters, 52, was fatally shot in his vehicle at a busy intersection after being stopped by police, who suspected him of stealing flowers outside a local business. On Jan 27, Fairfax Commonwealth’s Attorney Raymond Morrogh announced that his office would not file charges against the unnamed police officer involved in the shooting.

In Pete Earley’s words, Morrogh ...

... offered this stunning summary of what happened: "Unfortunately, we had a mentally ill man who was behaving bizarrely ... His family indicated he was behaving under delusions, that he might feel he was under attack if approached by the police. I think that's the explanation for his actions."

Pete is quick to point out that this is pure speculation on the part of the prosecutor, who apparently felt that an after-the-fact determination that Masters must have been crazy was reason enough to fire two rounds into him. As Pete points out:

The three officers did not know that Masters had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder when they confronted him. Many drivers open their jackets to retrieve their wallets when stopped by the police. The fact that a driver might be belligerent or challenge the police when confronted is not some automatic signal that he is mentally ill. What proof does Morrogh have that Masters was in the midst of a psychotic or delusional episode when he was stopped?

Pete also notes that “Morrogh's statement implies that individuals with mental illnesses cannot control their disorders and are prone to violence,” and that “even if Masters's disorder actually was a factor, there is an excellent chance that the officers who confronted him were not trained in how to determine whether someone acting ‘bizarrely’ is psychotic.”

Pete goes on to say that Crisis Intervention Training (CIT), which teaches police how to respond to situations involving individuals with mental illness, was offered to Fairfax Police in 2008, but has not been offered since.

Why are we not surprised?

(Note: Lest we rush to judgment, there is nothing in Pete's piece to suggest that the officer involved should be charged in the fatal shooting. That is obviously a separate issue. The concern here is the prosecutor's outrageous disregard for a citizen his office is charged with serving and protecting.)

Labels:

bipolar disorder,

CIT,

Crazy,

Fairfax,

John McManamy,

Pete Earley,

police,

Washington Post

Monday, November 2, 2009

Misdiagnosis - Patients Tell Their Stories

I write a very different blog on HealthCentral's BipolarConnect. There, I take a backseat to my readers, bipolar patients and loved ones. Nearly a month ago, I asked them:

Were you misdiagnosed with depression or something else? How long did it take before you finally received the correct diagnosis?

Readers began telling their stories over the next days and weeks, which I assembled into three blog pieces. The narrative is sobering and instructional:

"Jane's" response is fairly typical. She was diagnosed with depression at age 16 and prescribed Zoloft, “which was making me like a bunny on mass caffeine consumption.” She was put on Paxil, but her depression worsened and she gained 40 pounds. Unable to hold onto her job, she found a new doc, who “cocked his head, asked about my family’s mental health history ... and asked me ‘Did anyone ever ask you if you thought you might be bipolar?’"

Finally, on Lamictal, she has her life back, but "I spent 11 years on the wrong meds and destroying my life because I was misdiagnosed.”

What is coming in loud and clear is that a misdiagnosis of depression is all too common, with years on antidepressants that only worsen one's unrecognized bipolar. Since we tend to seek help when we are depressed rather than manic, it is not surprising that we receive the wrong diagnosis at first instance. But then the problem is compounded by psychiatrists who refuse to listen. As "Rachel," who waited 14 years for the correct diagnosis, describes it:

My major complaint with this whole debacle is not that I was incorrectly medicated, it is that I was incorrectly medicated because an entire comprehensive mental and physical inventory was never taken. AKA no one ever TALKED to me about what I was feeling and why I was feeling it. No one had mined my data for facts and established a clear pattern of my behavior. The first person who did that was me. ... They didn't do their job. Much like getting a bad mechanic job, my tranny dropped out on the freeway and my vehicle hit the wall going 75 - a complete loss.

Doctors who don't listen - that has been by far the number one complaint I have received from readers ever since I began writing about bipolar more than 10 years ago. As "Lorraine," who suffered with antidepressants for three years, writes:

The doctor (as many are) was a know-it-all and rarely listened to me. The doctor rarely considered how I felt. The doctor thought no one could ever know more than this one. The doctor rarely even considered the possibility of what I was feeling.

Why does it take so long for doctors to get smart? "Georgine" responds: "I believe it was because I was diagnosed with [depression] before so instead of trying to find out what I needed, the docs took the previous diagnosis and just agreed with it."

It took 25 years before a doctor finally corrected the original error.

And this from "Eva":

It was only when I got old and ugly that a doctor finally said, ya man, she's depressed, and she's bipolar. ... When I was young, beautiful and well-groomed, I looked like a female high-powered executive. On top of the world to the doctors who saw me. They dismissed my claims of depression, as ridiculousness. What does she have to be depressed about? Now that I'm old, ugly, unfashionable, I'm believable.

Our own ignorance and denial is another factor. As "Lilly" reports: “I stayed in denial successfully with alcohol and pills.” At last, during her third hospitalization, “I finally opened up a pamphlet on bipolar.” She took her meds as directed, and “was able to see reason. ... I’ve been struggling with this disease for over 25 years since I had turned 16 years old and I was 40 when I excepted it as something I would have to live with and take care of for the remainder of my life. Life is good now.”

***

There is no substitute for listening to real accounts from patients and loved ones. You can check out the full conversation at Bipolar Connect in the comments to my original question and a follow-up question, as well as my three pieces and the comments to these pieces:

Misdiagnosis - Eight Readers Tell Their Stories

Misdiagnosis - The Dialogue Continues

Misdiagnosis - Readers Tell Their Stories

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)