Continuing from my previous blog on mindfulness, from a book I'm working on about bipolar recovery ...

How powerful is mindfulness? Several years ago, on the dentist’s chair, I mindfully observed myself in a state of sheer panic. An assistant placed a suction tube into my mouth while a very understanding dentist fired up her drill and bored into my tooth. Gripping my armrests, I willed myself to remain seated as I heard the terrifying high-pitched screech of whirring metal against enamel. I felt water droplets and microscopic particles of tooth against the insides of my cheeks. She’s going to strike a nerve! I know it!

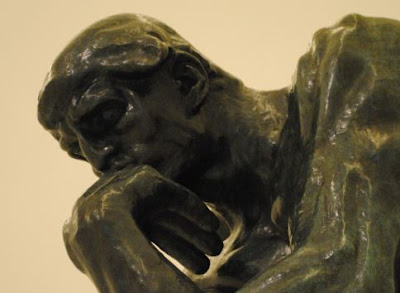

In the state I was in, there was no way I could fight that thought. The trick - and this is where the rubber meets the road - was for me not to attach myself to that thought. I was in a state of high panic. But what prevented me from giving into that panic was that part of me that seemingly hovered from above, dispassionately observing what was going on below, as if I were watching the grass grow or the paint dry. I’m guessing my panic scared the dentist and her assistant every bit as much as it did me. Somehow, we all got through it.

Attachment and non-attachment are recurring themes in Buddhism. Attachment - to our fears and desires - lies at the root of our suffering. Conversely, non-attachment is the key to happiness. Random thoughts have a way of sticking to us like fuzzy objects to Velcro. If we allow them to gain traction, they take over and pull in every unwanted emotion. That relationship break-up that happened five years ago? Suddenly out of the blue, totally unconnected to what’s going on around you right now, you’re feeling both longing and anger. Here we go again, your brain has been hijacked. The elephant has stampeded. All you can do is hold on for dear life.

A lot of us, if given the choice, would opt to simply wipe our memory clean, along with other events in our lives. But it’s not the events that are doing us in, it’s the thoughts of the events. Big distinction. While we can never undo the event, we are capable of forming a better relationship with our thoughts. Instead of fighting them, we can bring them out into the open where they lose some of their force. This is psychiatry 101.

But in the context of our discussion, the focus is a bit different, directed at our erroneous thinking. Like driving in traffic, we catch ourselves making a wrong cognitive turn and make an immediate course correction. At first, the mental effort is all white-knuckles. Damn! A false equivalence cut into my lane. Bastard! Watch where you’re going! Shit! Confirmation bias barreling down on me. Son of a bitch!

But with practice, as we begin to spot the hazards much earlier, we make the appropriate adjustments with far less drama, to the point where we’re almost driving on autopilot. It’s as if the brain actually knows where it’s going. Hallelujah!

But this is the ideal. Are you willing to settle for much less? Say a ten percent improvement? Let’s think like a statistician: A world-class sprinter who improves his time in the hundred meters by ten percent is going to beat Usain Bolt by ten meters. A politician who gains ten percent on her opponent is going to win in a landslide. In our own lives, that ten percent could make the difference between keeping your job and losing it, of staying in a relationship or finding yourself on your own, of thinking with greater clarity or losing your words.

Worth it, then? Of course it is. The catch is getting started. Meditating for say ten minutes a day is a good way to begin, but when you’re depressed, who wants to meditate? Even when we’re doing well, meditation is a big chore. You can go to mindfulness classes and tune into mindfulness videos and audios, but this is a major commitment. Your best bet, then, might be to purchase a mindfulness app. We’re so tethered to our phones anyway that setting aside a little time for mindfulness won’t be too much of an imposition.

Some of these apps are aimed at quieting the mind or guiding one into a meditative space. What we’re looking for here, though, is one that assists us in sharpening our thinking. Some of these come with monthly subscriptions, but a good many have free options. I cannot personally vouch for any of these apps or for mindfulness apps in general. What I can vouch for is mindfulness as a way of life. I am as far away from being a master at it as I am from being a concert pianist, but the little bit I’ve learned to apply to my life has made it one worth living. Please, you owe it to yourself to give it a try. Three words: You are worth it.

John McManamy is the author of Living Well with Depression and Bipolar Disorder and is the publisher of the Bipolar Expert Series, available on Amazon.